🎨 Reflections on Art 🪞 (Part 1?)

by BL SHIRELLE

July 29th, 2022 was a day for the history books. Beyoncé dropped Renaissance and it felt so good to be Black and Queer. Every song was empowering with a hidden sample or ode to past generations of house, ballroom, and disco legends but that’s a whole different blog. Truthfully, when I listen to that album my only pronouns are That/Bitch. I listened to it for two weeks straight, feeling productive as ever! During this period one of my faves, Rod Wave, was dropping so I had to give him a spin. I cut the album on and the first thing you hear is Rod belting, "You ever feel like you worthless😒…." No cap I had to cut that shit off. Not right now Rod…not right now…😭

I've been spending a lot of time appreciating different artistic practices lately; plays, musicals, and stand-up comedy, etc. Perhaps no medium is more important than the other, but a few trips to the Yale University Art Gallery and the Yale Center of British Art were the most impactful in my travels as of late. Aside from Simply Naomi and I being followed by a security guard to the point that I had to formally file a complaint, (smh…still nigga) my Blackness was on trial for another issue.

In the West African Art exhibition, I was enamored with headdresses, masks, jewelry, and sculptures. I must have spent thirty minutes looking at the intricacy of the carving of some elephant tusks. I was amazed, trying to encode something so beautiful. I could immediately see the cultural, social, and religious relevance to damn near each piece. I could feel why young warriors would want to adorn themselves with an elaborate mask to draw courage from past generations. It was all so intentional, and detailed, always drawing from or giving to entities outside of themselves. What I also appreciated about most of the art is it actually has a purpose. The masks, ceramics, armor, etc… it wasn't just for people to stare at or listen to, the beauty of it was just an addition to their actual use. The creativity in the themes, and the abstract representations of spirits; all left me feeling quite a few emotions: Inspired, strong, uplifted, and grounded.

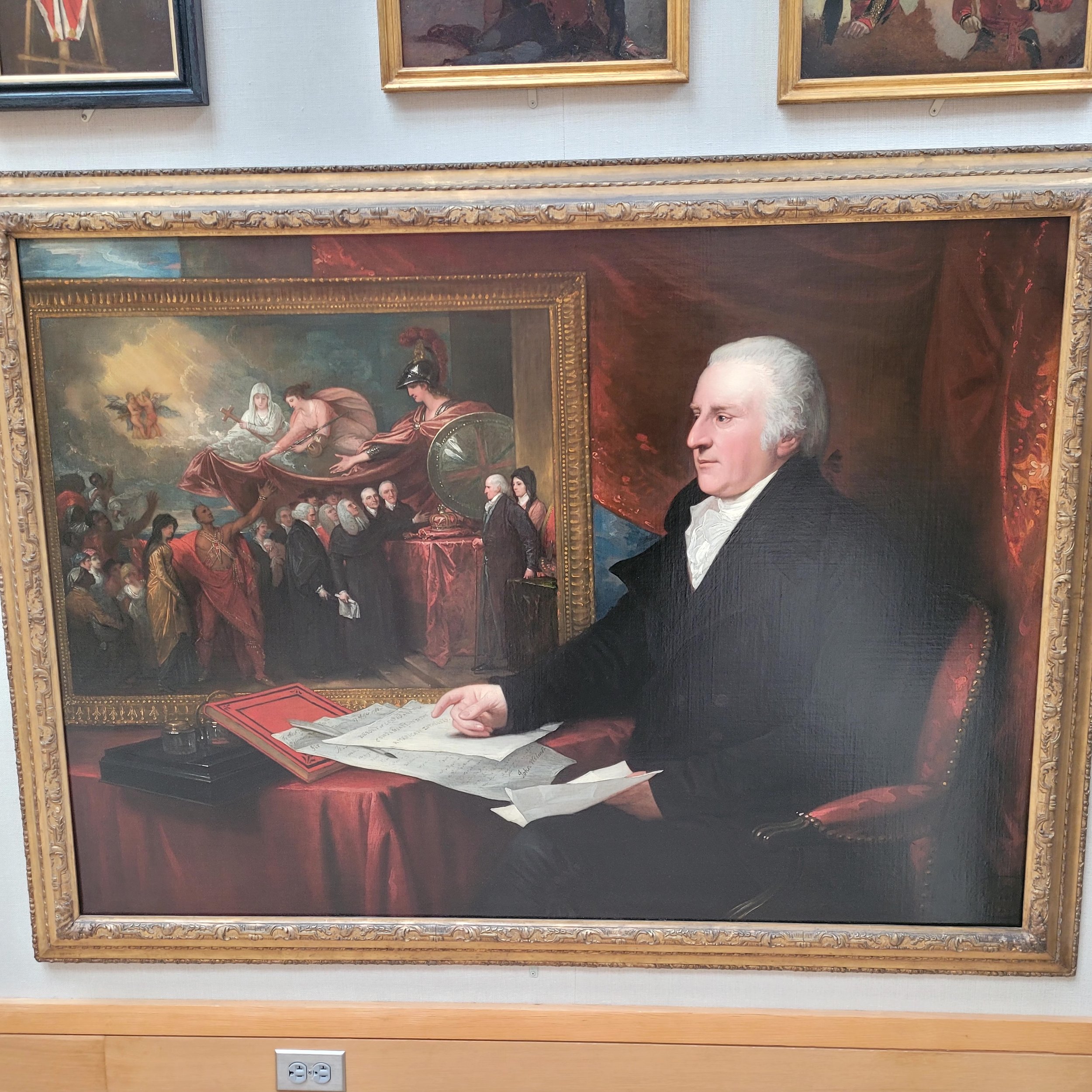

Then I went to the British Art Gallery and had a completely different range of emotions. I was not particularly inspired by the majority of oil paintings showcasing landscapes and self-portraits. A lot of it was displaying the mass wealth obtained by the colonial empire, and some of it was upholding religion in a theoretical sense, but it had something in common with West African Art. It was remarkably self-preserving. It's like… "Yes, it's 300 years later and I'm ugly as hell but here you are… staring at me” 😌 Lol. You know what? I respect that. Even the Greek art that honors their gods is created by depicting the image of man. I left the museum that day feeling the vanity of the purpose of art, but also the edification of the heritage it belongs to.

Then I went to the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, South Carolina and I saw this piece from one of the most notable, accomplished Black American artists in the world, Kara Walker. The piece was called "The Katastwóf Karavan (maquette)". To be honest with myself and you… it pissed me off. It pissed me off stylistically, and even from a historical perspective. I mean 500 years from now when archeologists are digging up artifacts after the zombie apocalypse, (my theory, don't judge lol) who are the neohumans (again, my thing) going to think Black Americans were if they only had our art to determine?

Then I started thinking about our mainstream music, which by all accounts has become more low vibrational over the past decade. Yes, gangsta and streep rap is as old as the genre itself, but the vocabulary, the wordplay, the brain power necessary to be a good rapper is non-existent. I thought about my relation to music and how for a very long time, up until recently it was essentially a very personal trauma dump that I was willing to share with the world. I thought about the rollout of Assata Troi and how it was gravitated to the fact that my mother and I sold drugs together. How my friends would say stuff like "you gotta market your shootout with the police better." Sometimes I feel like some Black Americans and White liberals have a sick love affair with our oppression. If that's not the case then at the bare minimum, our trauma is big business.

Don't get me wrong, I'm not saying we shouldn't detail white supremacism's causes and effects through art. I do indeed find that necessary. My issue is that mainstream art seems to only be interested in our struggle. Meaning the masses equate Black to trauma, but more importantly, the next generation is being consumed by the horrific things that have been done to us versus being inspired by the opportunities they have that prior generations did not. Even with all this recollection of struggle, I'm watching some of our youth resent our history. The power ballad R&B singer has lost their rightful place in the mainstream, we haven't had a crossover gospel hit in a decade (which we could always count on as a culture faith aside), and it's cool to wear shirts that read "I am not my ancestors." I think to myself we sure aren't. Imagine trying to organize a bus boycott in 2022. We can't even boycott Gucci 🤷🏾♀️. This mainstream struggle has made it almost impossible for intellectuals to fathom Black responsibility. I resent that. As I step in my power more and more I don't like to hear my people talk about what they can't do because some scholar who never lived their experience is telling them white supremacy makes it impossible. I wish Black joy was more cool, more marketable. I wish we could have a better balance between our pain and our pleasure. For every BL Shirelle on my block there were multiple homeowners and business owners. My family were indeed the outliers. I understand my career choice involves me hearing and seeing some of the most unfortunate outcomes this country has to offer. However, you who are reading this, ask yourself: When you engage with Black people, our art, or our culture, is it only from a lens that makes you feel bad for us? Is it only from a standpoint of us being oppressed? Do you engage with everyday Black folks and laugh with us? Celebrate? Enjoy your time in the most positive way possible? If not…this blog is for you.

If deep down you know I'm speaking to you, it does not make you a bad ally. We are all works in progress. It's just something worth taking a look at if you're interested in demonstrating anti-racist practices. I recommend a trip to The Colored Girls Museum. The Colored Girls Museum is a public ritual for the protection, praise & grace of the ordinary Colored Girl.

I love y'all and thank you for entertaining my innermost thoughts.

I sat down and spoke with two DJC visual artists who I highly respect in an attempt to process my emotions and learn about their thoughts on the current state of Black art and culture. I hope you enjoy their perspectives as well as their pieces.

H E N R Y “ S A N D M A N ” F U L L E R

Henry “Sandman” Fuller is a multi-talented artist, instructor, entrepreneur, and visionary. Born and raised in City Heights, Greenville SC, his journey started as a traditional graphic artist and cartoon illustrator for NationTime Newspaper in Jamaica, NY. Sandman is the Founder of the Character Thru Art Workshop and Mural Program for the Palmetto School District. He’s currently serving 30 years in the South Carolina Dept. of Corrections. An expert renderer, Sandman has a concentration in realism and has created over 500 murals.

BL: In your opinion, what’s the current state of art for Black American artists?

Sandman: Now more than ever I feel we are seeing the effects of the trauma we’ve been experiencing as a people. Especially in music, it seems to be a trauma response embodying our identity and how strongly it’s still connected to slavery unfortunately. Have you ever read The Wretched of The Earth by Frantz Fanon?

BL: I’m somewhat familiar with some of his theories in regards to decolonization…

Sandman: One of the ways in which colonial forces oppress colonized individuals is through the erasure of Black culture. Racist colonial powers claim that colonized countries are devoid of culture and meaningful artistic expression. This absence of culture is considered the height of barbarism.

BL: Okay, so when do we address the negatives in our traditions from an angle of accountability? I’m not going to lie, I'm a bit exhausted with the fact that it seems as though we struggle to formulate responsibility from a cultural perspective for the things we perpetuate. Until we do we’ll remain in the same state.

Sandman: It’s true, we’ll do things to our own that we would never contemplate doing to other races…

BL: Yeah, or if someone sees their enemy in a “white” space they’re less likely to be so brazen. Which is a direct tie to white supremacy but at the same time once you realize you hate your brother because you hate yourself – then you have to start looking inward and I feel like that’s where we stop a lot of the time.

Sandman: Yes, I think that in my experience I had to go to extreme measures to break through.

[Our connection goes bad and Sandman tells me to physically signal whatever I'm saying because he can't hear me. I signed one letter at a time and when our connection came back he started teaching me the full words and phrases that I was saying…]

BL: Do you have someone in your family that's deaf? How did you learn to sign so well?

Sandman: So back to that breakthrough I was telling you about. I was in supermax for six years, and when I started looking inward I actually ended up going on a verbal strike for two of those years. During that time I did nothing but read and take in information – it was less about me and what I thought. It's funny though because over time guards thought I was deaf and they used to get me extra food and contraband and stuff [laughs].

I had to learn sign language if I wanted to communicate. I mean, I had nothing but time to learn it. Coming out of that breakthrough was when I began to really appreciate artists such as Kehinde Wiley and Frank Morrison. A lot of their work embodies a very full Black experience and I love that. In fact, that mural of mine that you love is directly inspired by Frank Morrison.

BL: The one that I took the picture in front of.. . yes I see that.

Sandman: Yes, so it embodies a lot of things Black culture tends to not highlight. Not that we don't have it, but it's not highlighted. So the father is over in the corner playing with the daughter. It moves the spirit in a heartfelt way. Kehinde Wiley was inspired by the Good Times painter Ernie Barnes. That style is called Elongated Spirit Form. It's a beautiful art form that calls on the spirit of our ancestors. That's why the bodies tend to be stretched because they are filled with spirit, or gifts from past generations.

BL: Can you recall a spirit overtaking one of your pieces?

Sandman: Yes, people are going to think I'm crazy but… [laughs] One time [in the supermax] I was up for three days straight high off peppermint, coffee and chocolate chip cookies and I went inside the canvas…

BL: You went inside the canvas 😳

Sandman: Yes, I went inside the canvas and the colors were telling it where to move. It was the most compelling experience as an artist. I think if more artists led with spirit instead of mainstream motivation we would have better quality art overall. It's important for us to inspire the next generation to get to the next level. We have the power to change the narrative.

Photo: Jacob Blankenship for Bham Now

T A M E C A C O L E

Tameca Cole is a DJC visual artist and writer from Birmingham, Alabama. While serving 26½ years in the Alabama Department of Corrections, Tameca discovered her passion for art through Auburn University’s Alabama Prison Arts and Education Project. A quick learner, she soon discovered how cathartic creating art could be. That creative drive expanded when she began crafting collages for DJC art shows and receiving not only acclaim but also sales. Her trajectory since being released in 2016 continues to elevate. Tameca has shown work at Art Basel, MoMA PS1, and Martos Gallery, and has been featured in articles for Forbes, NY Times and Frieze Magazine.

BL: In your opinion, what’s the current state of art for Black American artists?

Tameca: Music-wise I’ve been noticing that we have the younger generation – I'm not knocking them, I listen to them too – but as an adult I'm mature enough to make things metaphorical. I don't think children's minds are developed enough to do the same and because of that, overall we have very low vibrational mainstream music which is directly (not solely) but participating in dumbing down our youth.

Visually, even if by default there's a demand for Black artists and female artists getting proper due and seeing the beauty of what we create, there's more to be done. In prior generations, typically African Americans artists got equal footing when they were really old or really dead [laughs]. So it's important for us to take advantage of this opportunity.

BL: What do you appreciate about art?

Tameca: I take in art no matter the background or ethnicity. I like to see people express themselves in a creative manner. It's inspiring and it connects us to people outside of our demographics, opens our worlds up so to speak…

BL: How much do you think oppression influences Black art?

Tameca: It definitely does quite a bit, I’ve been through that phase. Even if it doesn’t happen to a person directly it can still affect them.

I made a conscious decision not to be oppressed because I spent 26 and a half years in prison being oppressed so I decided to get away from that mindset. I'm a free spirited person and a lot of my best pieces are free spirited.

BL: Do you think the oppression expressed in art reinforces the oppression?

Tameca: I can’t continuously engage in taking in Black violence. It's depressing, it has a negative effect on me and I don't want that type of energy consuming me. How can I elevate myself above that?

If all the music consists of getting money, killing opps, over and over it becomes a part of your makeup if you're still developing. You gotta be sure of who you are to intake that stuff so heavily. I used to say I have real enemies, but I don’t say that anymore. Instead I say it's lessons I have to learn. That mindset has changed how I deal with people and how to cut negative people out of my life. I've grown from that. Peace is what I love, peace of mind. Though I'm still on paper [parole], I want to be as free as possible. I don't want to pollute my mind to the point where I forget it's so much more to life.

BL: Back in the day we sent messages through art. How much of that is necessary for the future?

Tameca: Depends on where the artist is in life. You want to be able to communicate with people who look like you so they can feel it in their soul and are inspired by it. That’s what made gospel rap start to catch on. We can speak on things outside of police brutality, woe is me just because I’m Black, the product of my environment is worn thin at this point. We have Black millionaires and billionaires. We can’t create excuses in our art. We have to have art that encourages and invigorates. The system wants to sweep things under the rug and in those instances we need to notate from a historical perspective if you're compelled to tell that story.

BL: I agree. That reminds me of my motivation to write the music for Echoes of Attica. Too many people don't know the history behind that, so informing through art creates a much more vulnerable environment to take in an atrocity as crazy as that one.

In your opinion, who is responsible for the commercialization of the Black struggle?

Tameca: It's definitely a combo. They dangle a carrot in front of your face to exploit your struggle. the artist may want to talk about their love for their baby mom, or being a regular person. If you look at the charts and see the competition is “Shoot 'em up bang bang” and your message is not penetrating the market, you're more likely to adapt to the status quo.

NBA Youngboy is one of the youth that I actually feel the pain of, but not in a glorifying manner. Our biggest rappers of the last decade aren't gangster rappers when you think of Drake, Kendrick, and J. Cole…

BL: They aren't but they also are the ones whose fan base is not predominantly Black.

Tameca: That's very true. However, good, uplifting music is around. The audience gravitates to what they want. The responsibility is more so on the audience than anyone else. Artists are just mirrors of society. Now more than ever – you don't need a label, an industry push or a cosign to do your thing. It's just like a social media algorithm, if you're only seeing negative things on your timeline that's because you spend more time taking in that kind of content. Ask yourself why that is. Maybe then we can start getting to the root of our collective trauma.

“Trees, Jim Crow Weapons of Choice”

“Spirits Song”